- Meniscus tears are extremely common. Among the general population, they have an annual incidence of 66 per 100,000 people.2

- There is not much research regarding exercises that can specifically prevent meniscus tears.

- Treatment can be non-surgical or surgical, depending on various factors

Anatomy & Physiology

Even though it appears that the knee only moves in flexion and extension, there are far more planes of motion than meet the eye. In addition to these two motions there is also rotation and lateral movement (termed varus and valgus movement in medicine). The knee (Figure 2) consists of 4 main bones:

- Femur

- Tibia

- Fibula

- Patella

These bones form 3 joints in the knee:

- Tibiofemoral joint (the main knee joint)

- Patellofemoral joint (where the kneecap glides on the thigh bone)

- Tibiofibular joint (Mentioned here for completeness. It is less important in this discussion and less frequently injured compared to joints 1 & 2)

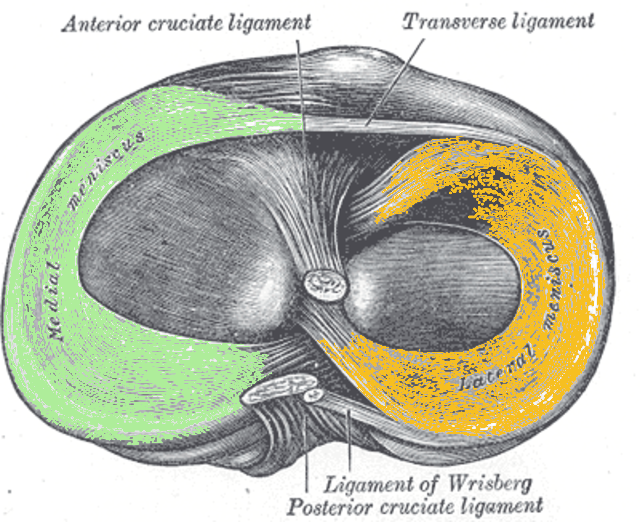

So, what holds these bones together? Extremely simplified, the predominant structures include the menisci and ligaments. There are 2 menisci called the medial meniscus (medial means inside) and lateral meniscus (lateral means outside). The main ligaments that people talk about are the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) (Figure 3). Our focus here is the tiny C shaped menisci (Figure 4).

You might be thinking: “how can these little structures cause such a big problem?” It is an excellent question. In the mid 1900s we used to remove a torn meniscus, and this led to rapid degeneration of the joint (in other words, early arthritis). The menisci provide shock absorption, increase joint congruity, and convert compressive forces provided by the body to tensile forces. Our menisci are thought to bear 40-70% of the load transmission across the joint. During walking, forces can go up to 300% body weight and during running, forces can exceed 4-8x that!3 So, I’d say these structures are quite important. For these reasons, us crazy Orthopaedic Surgeons spend a ton of time and energy trying to repair the meniscus whenever possible. More on this in the treatment section.

Figure 5 MRIs of meniscal injuries. Green arrows show sites of injury. 5a and 5b are different views of a medial meniscus injury of one patient. 5c is a lateral meniscal injury of another patient.

Conservative (that is, non-surgical) versus operative management is decided on a case-by-case basis. This depends on many factors including a patient’s age, body mass index (BMI), activity level, type of tear, and associated injuries. Conservative management consists of physical therapy. Operative management includes partial meniscectomy (fancy wording for removing the torn portion) versus repairing the meniscus. Degenerative tears are typically seen in older patients or young patients who waited to seek treatment and kept grinding away at the tear. These tears can often be treated nonoperatively. A randomized control trial by Katz et al compared patients over the age of 45 with some arthritis who were either treated operatively with meniscectomy or nonoperatively with physical therapy alone. They showed no difference at 12 month follow up, although there was a 30% crossover of patients from nonoperative treatment to operative treatment.4 These patients did the same as patients who had surgery immediately, which means that trying conservative care first in these degenerative tears is a great option. In addition to physical therapy a brace can be added if the patient would like one. There is limited research for or against the use of a brace, so they are seldomly used in my practice unless a patient really wants one. Contrary to popular belief, there is no literature to support the claim that braces cause weakness of the muscles surrounding the leg. So, if you’d like one and it doesn’t interfere with jiu jitsu (which they typically do) then go for it.

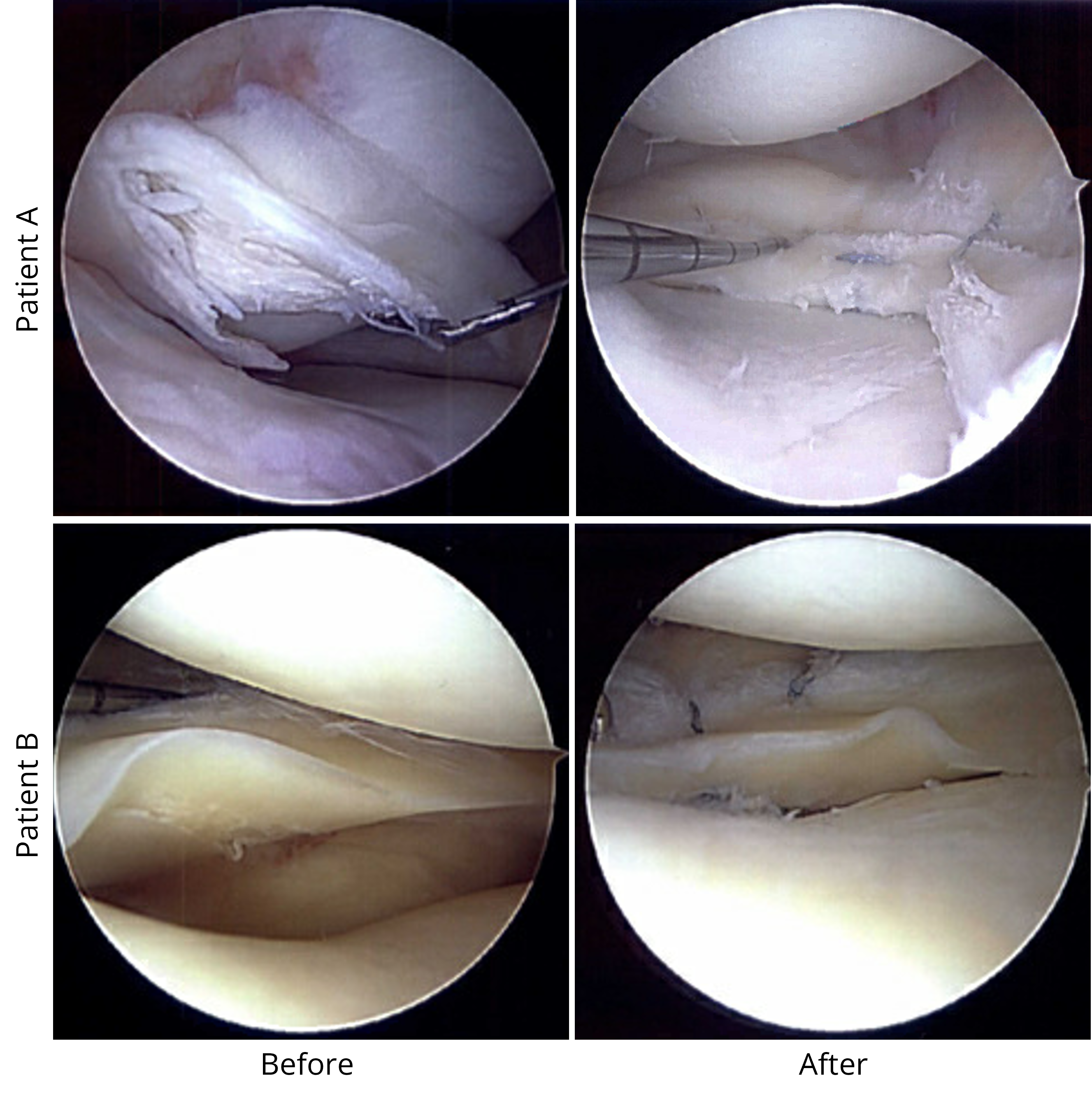

As previously discussed, there is commonly an ACL tear along with a meniscus tear following a substantial twisting type injury and a loud pop. In these cases, surgery is often recommended. ACL tears can be treated conservatively for older patients, particularly in athletes who perform straight line sports (ie: running, cycling, swimming). In my young jiu jitsu athletes with combined ACL and meniscus tears, I often recommend surgery to prevent recurrent injuries and the potential for further damage. For fixable meniscus tears in younger patients, I typically recommend early surgery (within 3-4 months) to avoid worsening the tear. When surgery is needed, I am a proponent of trying to fix every meniscus possible because it has been proven in the literature that removing meniscus results in rapid, deleterious effects on the joint. There are many techniques for meniscus repair. Figure 7 shows intraoperative pictures of the two jiu jitsu athletes whose MRIs are above. I was able to repair their menisci and they both returned to sport between 4-6 months post operatively.

Conclusion

References

- Hinz M, Kleim BD, Berthold DP, Geyer S, Lambert C, Imhoff AB, Mehl J. Injury Patterns, Risk Factors, and Return to Sport in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu: A Cross-sectional Survey of 1140 Athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021 Dec 20;9(12):23259671211062568. doi: 10.1177/23259671211062568. PMID: 34988235.

- Mordecai SC, Al-Hadithy N, Ware HE, Gupte CM. Treatment of meniscal tears: An evidence based approach. World J Orthop. 2014 Jul 18;5(3):233-41. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.233. PMID: 25035825.

- Zhang, K.Y. et al.The relationship between lateral meniscus shape and joint contact parameters in the knee: a study using data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Res Ther 16, R27 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4455

- Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, de Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, Donnell-Fink LA, Guermazi A, Haas AK, Jones MH, Levy BA, Mandl LA, Martin SD, Marx RG, Miniaci A, Matava MJ, Palmisano J, Reinke EK, Richardson BE, Rome BN, Safran-Norton CE, Skoniecki DJ, Solomon DH, Smith MV, Spindler KP, Stuart MJ, Wright J, Wright RW, Losina E. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013 May 2;368(18):1675-84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301408. Epub 2013 Mar 18. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 15;369(7):683. PMID: 23506518.

- O’Donnell K, Freedman KB, Tjoumakaris FP. Rehabilitation Protocols After Isolated Meniscal Repair: A Systematic Review. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;45(7):1687-1697. doi:10.1177/0363546516667578

- Blanchard ER, Hadley CJ, Wicks ED, Emper W, Cohen SB. Return to Play After Isolated Meniscal Repairs in Athletes: A Systematic Review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(11):2325967120962093. Published 2020 Nov 20. doi:10.1177/2325967120962093

- Adams BG, Houston MN, Cameron KL. The Epidemiology of Meniscus Injury. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2021 Sep 1;29(3):e24-e33. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000329. PMID: 34398119.

- Gee SM, Tennent DJ, Cameron KL, Posner MA. The Burden of Meniscus Injury in Young and Physically Active Populations. Clin Sports Med. 2020 Jan;39(1):13-27. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2019.08.008. PMID: 31767103.

- Figure 2 was obtained via commons copyright permission, Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014“. WikiJournal of Medicine1 (2). DOI:15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436

- Figures 3 and 4 were obtained via public domain copyright. Henry Gray (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body.

- Other figures were created by author, patients involved gave full written consent complying with HIPAA guidelines.

Very interesting article, Dr. Jimenez. It is helpful to know what factors we can address to decrease our injury risk, or to at least know that we are at increased risk in some case.

Thanks for the feedback Jon. I’ll be posting more videos on exercises and other tips for various body parts soon on my Instagram! Glad this was helpful.