It was just another morning session at the gym. After warm up there was drilling. After drilling, situational rolling. And then a round robin shark tank with two-minute matches. Halfway through I was rolling with that one partner. You know the one. The one you roll with the most. The one who knows all of your moves and you think you know theirs to the extent that you probably both know how things are going in each other’s respective lives based on how the other person is rolling. Anyway, he got me in a sneaky baseball choke throw from standing, one I should have seen coming as he had been working on them the past couple weeks. But this time I thought I was still good and was working to get out. That is until I heard a train and then the next second somehow ended up feeling 100% drained of all my energy but simultaneously didn’t understand how I ended up in my open guard with him standing. Then when I fully came to I realized he was doing a passive leg raise and seeing how ghost white his face was with concern I realized I made the biggest mistake, the one I tell myself I will never do – not tapping early enough.

I know my story isn’t unique. I’ve talked to many people who have been put to sleep with a choke submission and have seen it many times at tournaments and professional MMA fights. Despite many in the grappling community being familiar with how to apply a choke, I am frequently asked about why and how they actually work. I’m also frequently asked, from a medical physiology perspective, what the difference between a blood choke and an air choke is. Lastly, I’m commonly asked if there is any lasting harm from being ‘choked out.’ Here are the quick bites if you’re short on time:

- The choke submission works by depriving the brain of oxygen

- This is done by stopping blood flow to the brain, oxygen from entering the lungs, or a combination of both

- Being choked out usually doesn’t lead to long term medical problems but …

- It’s preventable and the brain prefers to not be forced unconscious so tap early and tap often

Continue Reading: 10min Read

Pathophysiology

So what actually happens to someone if they don’t tap to a choke? This loss of consciousness in medicine is termed syncope. While the exact anatomical locations of the brain and how they physiologically function to produce consciousness is beyond the scope of this article (and still not fully understood by current medical science),1,2 we do know that multiple locations of the brain lose normal electrical activity. Most of our understanding of what happens to the brain during syncope caused by strangulation comes from a study done in 1943 investigating what happens to a patient and their brain when acute cessation of blood flow occurs. The three researchers created a device they not only named after themselves called the Kabat-Rossen-Anderson apparatus but also tested it on themselves before any other human test subjects. The KRA apparatus applied 600mmHg of pressure to the lower neck within a fraction of a second. Although controversial in its methods, rightly so due to its use of prisoners and schizophrenics as test subjects, their study did help to prove the reason WWII pilots were experiencing syncope after a rapid ascent from a dive bomb maneuver, leading to further research to help prevent this.3,4

The brain is one of the most metabolically active tissues in the body; in fact at rest the brain accounts for 15% of the body’s total metabolic energy demand yet it is only 2% of the body’s mass. This works out to the brain using 7.5 times more energy than other organs while a body is at rest. What’s more is that most of the brain cannot perform ‘anaerobic metabolism,’ which is how many cells in the body can function when there are times of low to no oxygen. Practically this translates to other organs in the body being able to function and survive for 3 to 30 minutes (depending on the organ) versus the brain which will go unconscious in 5-10 seconds without oxygen.3,5,6 If oxygen and nutrient perfusion are restored to the brain quickly after unconsciousness, no permanent neurological damage is currently known to be done and someone will typically regain consciousness in 4-10 seconds.3 But if the choke hold is not released and one continues without adequate brain perfusion it quickly can lead to cell death and permanent brain damage (usually after 2-4 minutes) or worse brain death (usually after 6-10 minutes).7,8,9,10,11

Anatomy

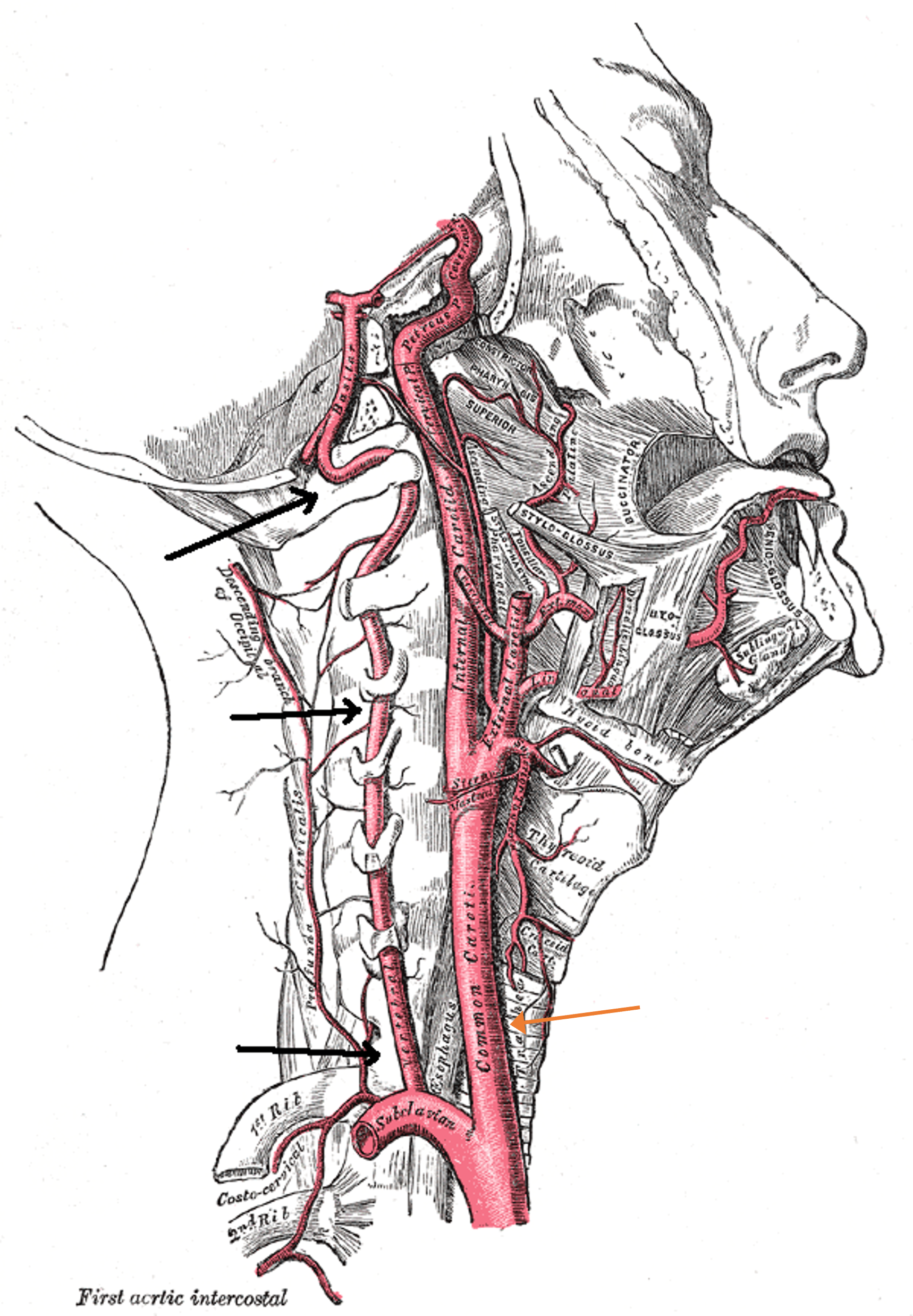

The difference between a blood choke and an air choke is the mechanism by which one’s oxygen supply is cut off. A blood choke technically occurs when the flow of blood in the carotid and vertebral arteries of the neck is shut off (see figure 2). This results in immediate cessation of oxygen and nutrients to the brain. An air choke however cuts off the flow of air in and out of the trachea, a.k.a. the ‘windpipe,’ to the lungs (see figure 3). It typically takes longer for this to cause unconsciousness as blood is still flowing and perfusing the brain and one will steadily have decreasing oxygen levels with no breathing. So in essence, the answer to how long an air choke takes to cause syncope is how long a person is able to hold their breath versus the 5-10 seconds for a blood choke.

Prevention and Treatment

Tap Early and Tap Often

This wouldn’t be a great medical article if I didn’t talk about prevention, so despite how obvious the following may sound it’s important to mention. The best way to prevent getting choked out is to protect your neck. More importantly, as you are training and learning to grapple tap early and tap often! I love to roll hard, I love to compete, but I also want to roll, ideally, forever. I know that there will always be times that I lose, and I’m ok with that. Yet despite living and rolling by this creed one can still make a mistake, like I did, and get put to sleep.

As you likely could have guessed, the best treatment for someone who has gone unconscious from a choke hold is to have the brain re-perfused with oxygen rich blood. The vast majority of people who go unconscious from a choke submission will be able to accomplish this simply by relieving the choke hold; this is because their heart is still pumping and they are usually still breathing. You may see people raise the legs of someone who has gone unconscious and while there is not a clinical trial comparing a leg raise versus no leg raise in people who have gone unconscious from being choked out, this isn’t unreasonable as long as the person falls into the majority who still have a pulse and are breathing because a passive leg raise can increase one’s cardiac output12 and has been shown to be an effective method of preventing syncope in people who are frequent fainters.13,14

Lastly there is a minority of people who, because of the shock or because of the length of time the choke hold had been held prior to release, won’t have a pulse or be spontaneously breathing. These are the ones that will need CPR. So if you know how to perform CPR don’t forget to do your primary assessment. If you don’t know CPR and thus don’t know what a primary assessment is I encourage you to take a half day out of your life to learn it. Most communities have multiple options for this, a lot of them free of charge.

Conclusion

I hope this has answered some of those burning medical questions about chokes. While currently there’s no hard evidence that succumbing to syncope by choke has any lasting harm as long as the brain is allowed to be rapidly re-perfused with oxygenated blood, for a minority of people who don’t have the latter happen it can lead to dire consequences. So why tempt fate when you don’t have to? As you learn the gentle art and how to apply choke submissions in numerous ways, be sure you understand what you are doing and what you are subjecting yourself to. I encourage you to roll humbly, tap early, care for and respect others and never stop learning.

References

- Hal Blumenfeld, Chapter 1 – Neuroanatomical Basis of Consciousness, The Neurology of Conciousness (Second Edition), Academic Press, 2016, Pages 3-29, ISBN 9780128009482.

- Morsella E, Krieger SC, Bargh JA. Minimal neuroanatomy for a conscious brain: homing in on the networks constituting consciousness. Neural Netw. 2010 Jan;23(1):14-5. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2009.08.004. Epub 2009 Aug 20. PMID: 19716260; PMCID: PMC2787707.

- KABAT H, ANDERSON JP. ACUTE ARREST OF CEREBRAL CIRCULATION IN MAN: LIEUTENANT RALPH ROSSEN (MC), U.S.N.R.Arch NeurPsych. 1943;50(5):510–528. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1943.02290230022002

- Smith BA, Clayton EW, Robertson D. Experimental arrest of cerebral blood flow in human subjects: the red wing studies revisited. Perspect Biol Med. 2011 Spring;54(2):121-31. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2011.0018. PMID: 21532128.

- Pana R, Hornby L, Shemie SD, Dhanani S, Teitelbaum J. Time to loss of brain function and activity during circulatory arrest. J Crit Care. 2016 Aug;34:77-83. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.001.

- Guyton & Hall, Chapter 61 – Cerebral Blood Flow, Cerebral Fluid, and Brain Metabolism. Textbook of Medical Physiology, 11th Elsevier Saunders, 2006, pp 761-768. ISBN 0-7216-0240-1.

- Hossmann KA, Kleihues P. Reversibility of ischemic brain damage. Arch Neurol. 1973 Dec;29(6):375-84. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1973.00490300037004. PMID: 4202405.

- Shemie SD, Gardiner D. Circulatory Arrest, Brain Arrest and Death Determination. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018 Mar 13;5:15. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00015. PMID: 29662882.

- Lee JM, Grabb MC, Zipfel GJ, Choi DW. Brain tissue responses to ischemia. J Clin Invest. 2000 Sep;106(6):723-31. doi: 10.1172/JCI11003. PMID: 10995780.

- Sekhon MS, Ainslie PN, Griesdale DE. Clinical pathophysiology of hypoxic ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest: a “two-hit” model. Crit Care. 2017 Apr 13;21(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1670-9. PMID: 28403909.

- Raichle ME. The pathophysiology of brain ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1983 Jan;13(1):2-10. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130103. PMID: 6299175.

- Monnet X, Marik P, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising for predicting fluid responsiveness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016 Dec;42(12):1935-1947. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4134-1. Epub 2016 Jan 29. PMID: 26825952.

- Williams EL, Khan FM, Claydon VE. Counter pressure maneuvers for syncope prevention: A semi-systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Oct 13;9:1016420. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1016420. PMID: 36312294.

- M J, S S, B N, et al. (February 01, 2023) Effectiveness of Leg Raise and Leg Fold Maneuver to Prevent Syncope During Extraction of Teeth: A Pilot Study. Cureus 15(2): e34488. doi:10.7759/cureus.34488

- Figure 2 adapted from Häggström, Mikael (2014). “Medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014.” WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.008. ISSN 2002-4436. Public Domain.

- Figure 3 adapted from Hoofring, Alan (2003). Published under public domain by the National Cancer Institute.

Recent Comments