Those who grapple have likely experienced some sort of mat funk either directly or indirectly. Mat funk is a nickname for a myriad of skin conditions that can occur from grappling, and given their different causes and thus different treatments they each deserve to be broken down and explained. Continuing the mat funk series, this month’s post is on impetigo. Here are the quick bullets, but for the deep dive, keep reading.

- Impetigo is caused by an infection from a bacteria.

- Impetigo is very contagious but easily treatable and preventable.

- While impetigo is typically not dangerous, it is one type of many ‘staph infections’ so if untreated can progress to something more dangerous.

Continue Reading: 10min Read

Overview and History

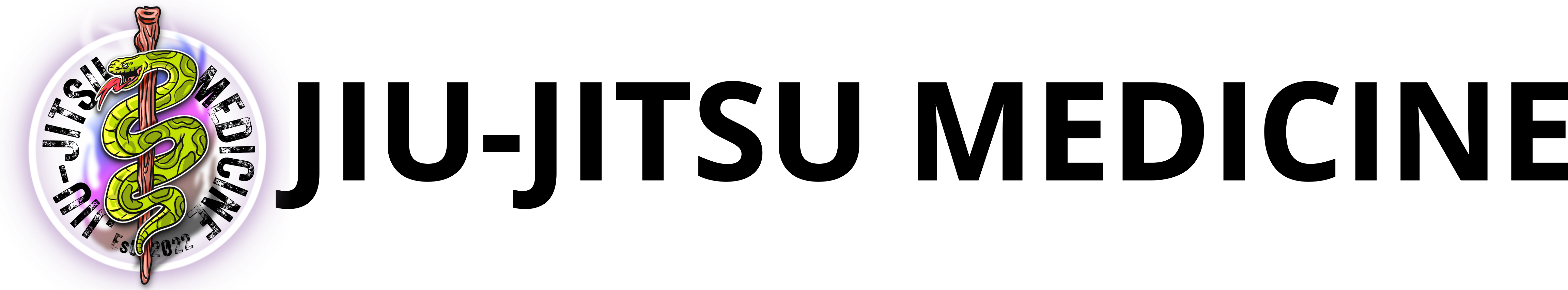

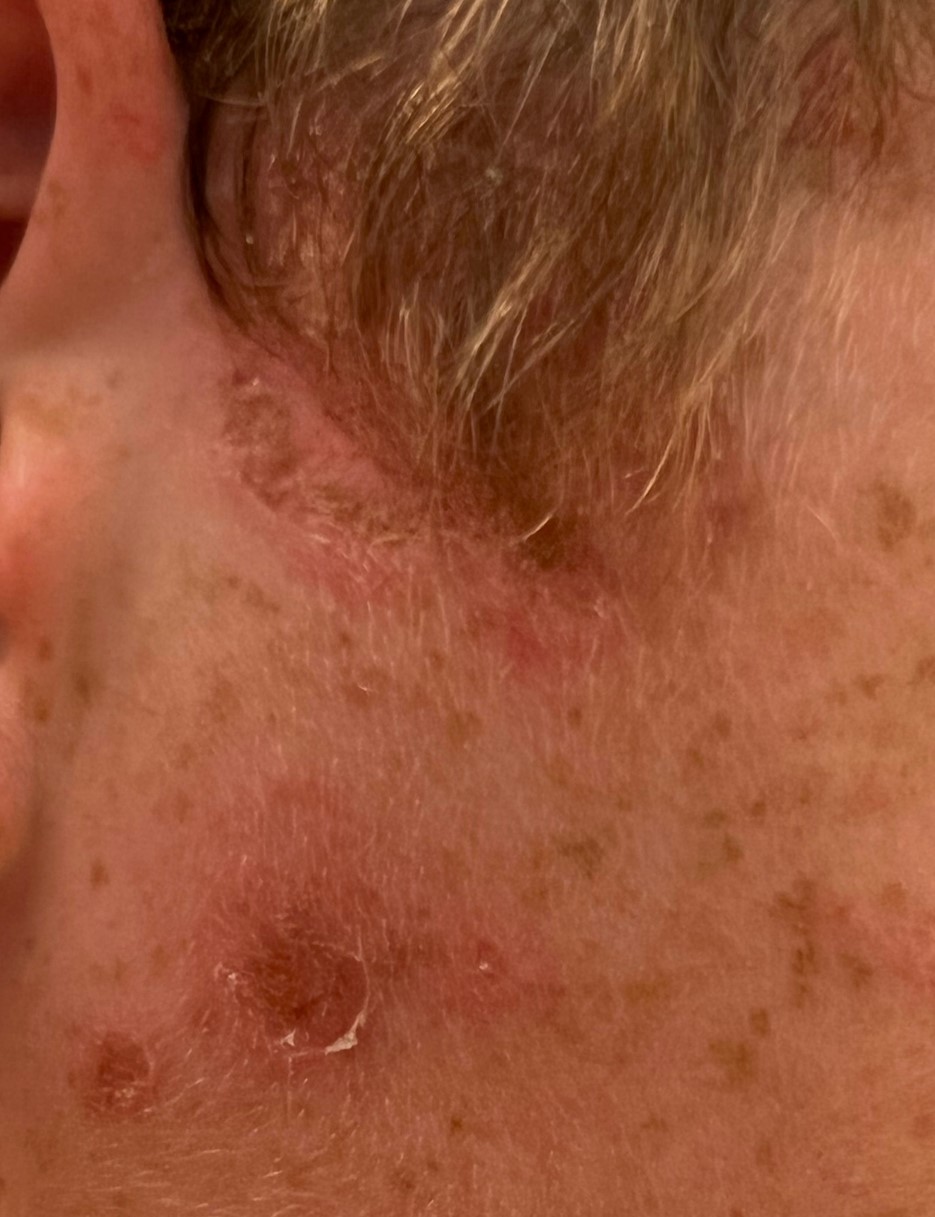

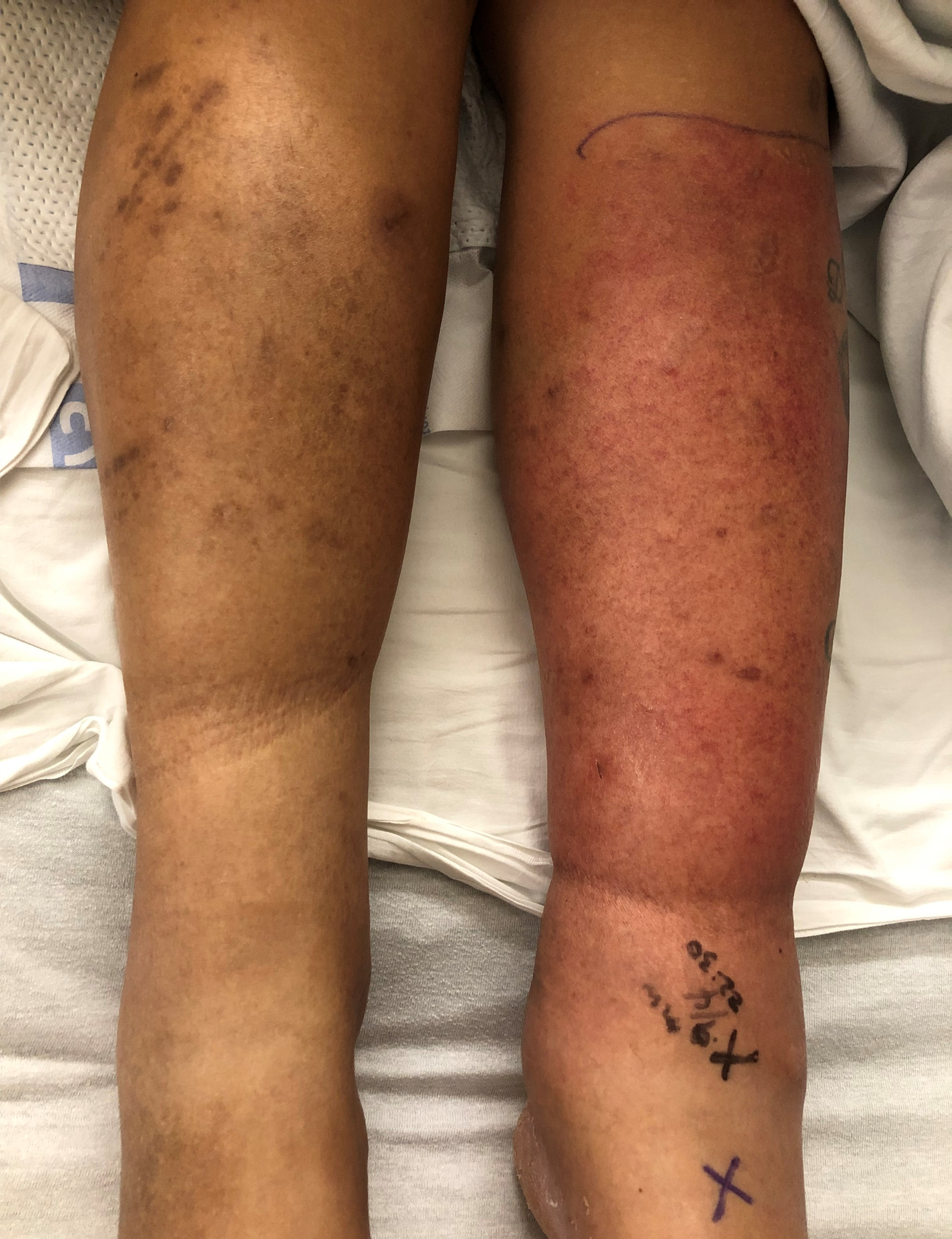

Impetigo is a skin infection by a bacteria. Most cases are caused by a bacteria called Staphylococcus aureus (see Figure 2). That’s why many will also refer to it as a ‘staph infection.’ That said, one other bacteria can cause it, a type of Streptococcus, but much less often.7 Both of these bacteria are able to infect many places of the body, and similar to ringworm, there are different layers of the skin that can be infected by these bacteria leading to different symptoms and often different treatment regimens for the same causative organisms. With impetigo, the bacteria infects anywhere on the body’s skin but specifically on its very top layer, and this is why most impetigo infections are able to be treated with a topical antibiotic or antiseptic therapy. Oral antibiotics can be used but usually are only necessary when impetigo is very extensive. Impetigo itself, while highly contagious, is not dangerous. That said, when these bacteria cause infection in different locations of the body (see Figure 3 for an example of a cellulitis infection), the story can be quite different; thus why it is very important to get it treated and not let it advance.

A brief word on ‘colonization.’ You may have heard that most people carry staph on their body already, living there on the skin not causing an infection (i.e. colonization), and this is true. Studies in athletes show that colonization prevalence at any given time varies from 34-62%, is highest in contact sports, and about 76% of them will be colonized at least once in a two year period.13,14 Once colonized, staph lives on the various places of the skin, especially in the opening of the nostrils to the nose and on finger tips.10,13 What’s more, those who are colonized are at greater risk for developing a skin infection, like impetigo. 13,14

So it’s logical to consider that actively decolonizing individuals of staph would decrease the risk of infection. There is so much to unpack here with regards to the medical literature, but let me summarize it this way. Yes, there are staph decolonization medicines (mostly topical) and washes that can and do decrease the risk for a staph infection occurring. The concern though is that most evidence shows it only works for about one to three months after the decolonization treatment (usually a 5-day course of topical antibiotics and special anti-septic bathing).8,14 And while monthly repetitive decolonization treatments do decrease the risk of infection more long term, they also increase the risk of producing resistant strains of staph (e.g. an even more resistant form of methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus or MRSA) and they disrupt good bacteria, aka probiotics, on a person’s body.14 So in summary, decolonization is usually only recommended for those who suffer from recurrent staph infections and have ongoing high risk behavior of colonization, like grappling.15

Conclusion

References

- Agel J, Ransone J, Dick R, Oppliger R, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men’s wrestling injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988-1989 through 2003-2004. J Athl Train. 2007 Apr-Jun;42(2):303-10. PMID: 17710180

- Herzog MM, Fraser MA, Register-Mihalik JK, Kerr ZY. Epidemiology of Skin Infections in Men’s Wrestling: Analysis of 2009-2010 Through 2013-2014 National Collegiate Athletic Association Surveillance Data. J Athl Train. 2017 May;52(5):457-463. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.2.16. Epub 2017 Mar 31. PMID: 28362160

- Kordi R, Mansournia MA, Nourian RA, Wallace WA. Cauliflower Ear and Skin Infections among Wrestlers in Tehran. J Sports Sci Med. 2007 Oct 1;6(CSSI-2):39-44. PMID: 24198702

- Yard EE, Collins CL, Dick RW, Comstock RD. An epidemiologic comparison of high school and college wrestling injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2008 Jan;36(1):57-64. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307507. Epub 2007 Oct 11. PMID: 17932400.

- REED CB. IMPETIGO OR PYODERMATITIS NEONATORUM. Arch Derm Syphilol.1928;18(1):26–36. doi:10.1001/archderm.1928.02380130029002

- Fox, William Tilbury. On Impetigo contagiosa, or porrigo. E-version reprinted by the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Accessed https://archive.org/details/b22315834/mode/1up

- Demidovich CW, Wittler RR, Ruff ME, Bass JW, Browning WC. Impetigo. Current etiology and comparison of penicillin, erythromycin, and cephalexin therapies. Am J Dis Child. 1990 Dec;144(12):1313-5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150360037015. PMID: 2244610.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of Recurrent Staphylococcal Skin Infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015 Sep;29(3):429-64. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.05.007. PMID: 26311356.

- Brancaccio M, Mennitti C, Laneri S, Franco A, De Biasi MG, Cesaro A, Fimiani F, Moscarella E, Gragnano F, Mazzaccara C, Limongelli G, Frisso G, Lombardo B, Pagliuca C, Colicchio R, Salvatore P, Calabrò P, Pero R, Scudiero O. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Risk for General Infection and Endocarditis Among Athletes. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Jun 18;9(6):332. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060332. PMID: 32570705.

- Oller AR, Province L, Curless B. Staphylococcus aureus recovery from environmental and human locations in 2 collegiate athletic teams. J Athl Train. 2010 May-Jun;45(3):222-9. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.222. PMID: 20446834.

- Young LM, Motz VA, Markey ER, Young SC, Beaschler RE. Recommendations for Best Disinfectant Practices to Reduce the Spread of Infection via Wrestling Mats. J Athl Train. 2017 Feb;52(2):82-88. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.1.02. Epub 2017 Jan 16. PMID: 28092165.

- Anderson BJ. Effectiveness of body wipes as an adjunct to reducing skin infections in high school wrestlers. Clin J Sport Med. 2012 Sep;22(5):424-9. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3182592439. PMID: 22695403.

- Jiménez-Truque N, Saye EJ, Soper N, Saville BR, Thomsen I, Edwards KM, Creech CB. Longitudinal Assessment of Colonization With Staphylococcus aureus in Healthy Collegiate Athletes. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 Jun;5(2):105-13. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu108. Epub 2014 Nov 5. PMID: 27199467.

- Karanika S, Kinamon T, Grigoras C, Mylonakis E. Colonization With Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Risk for Infection Among Asymptomatic Athletes: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Jul 15;63(2):195-204. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw240. Epub 2016 Apr 18. PMID: 27090988.

- Catherine Liu et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Adults and Children, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 52, Issue 3, 1 February 2011, Pages e18–e55, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq146

- Figure 2 adapted from photo in public domain from the CDC Public Health Image Library, ID #5147, 1984.

- Other figures were created by author, patients involved gave full written consent complying with HIPAA guidelines.

Great article!